8億円の茶碗での一服はいかに(愛知県名古屋市千種区姫池通 骨董買取 古美術風光舎)

2026.02.23

先日、某オークションにて初代楽長次郎の黒茶碗が、なななんと8億円にて落札されるという話を耳にしました

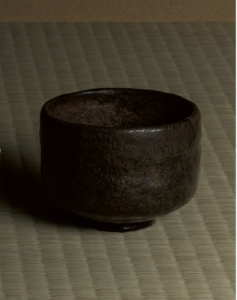

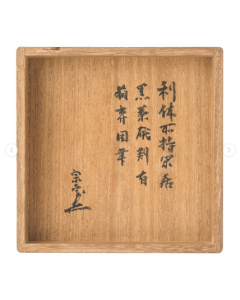

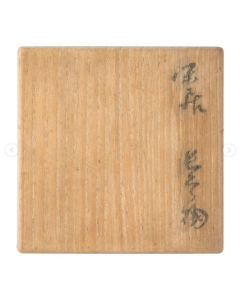

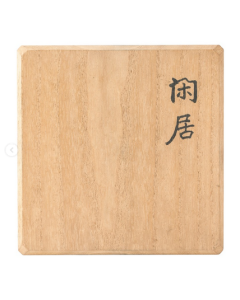

8億円です…。銘は「閑居」といいまして、高台内にうっすらと利休在判があり、仙蓋表の字は千利休・一燈極礼のものが記されております。銘品中の銘品です。画像ではありましたがあまりの銘品を前にすると、なにかインスピレーションを得ようと、その存在に吸い込まれしばし眺めてはいるのですが、なにせ知識と教養の無さによりどう表現してよいか難しい。ただただ8億円か…などと感嘆の声が漏れるばかりでした。

画像を拝見したところいたって素朴な黒楽茶碗なのですが、うっすらと何層にも色が微妙に重なり、その濃淡が様々な想像を掻き立てます。長年使われてきた茶溜まりや、消えかかっている利休の在判が残されています。手に取ることができるとたぶんですが、震えあがってしまうような銘品なのでしょう。それにしても、上手く表現できませんし、それすら恐れ多い気もしてきました笑。

それはそうと、なぜか作者の初代長次郎については生きていた時代の彼について記された文書は今のところ見当たらないようでして、どのような人物だったのかはわからないようです。生年不詳で天正17年に没したとされており、恐らく陶工の家系の一員ではあるようですね。

その初代長次郎がどのようにして千利休と出会ったのかももちろん謎なのですが、天正14年の茶会記などの記録から長次郎の茶碗についての記載が登場しています。これまでの銘物とは違った茶碗に、千利休もその価値観や理想を体現していく茶碗にどんどん魅せられていったのでしょうか。いかん、8億円の重みが拙い私の想像力をも刺激しますね。

初代長次郎の作品数は正確には特定されていませんが、現存する茶碗は数十作程度と推定されています。

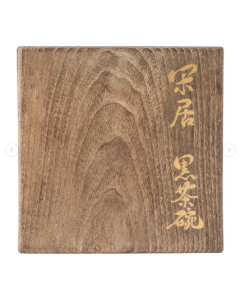

そんな利休の思想し作られた初代長次郎の茶碗の中でも、利休が所持し銘をつけたとられる代表的なお茶碗を「長次郎七種」あるいは「利休七種」と呼び特に珍重されてきました。その「長次郎七種」の中には内七種と外七種があるようでして、今回落札された「閑居」は外七種の一作のようです。また、茶人金森得水によって選出された「長次郎新選七種」にも数えられています。この「閑居」は今回このオークション出品のタイミングまで所在不明の作品だったようでして、そんなバックボーンもなんだか気になってきます。

そんな想像の域でしかつぶやくことしか叶いませんが、8億円の重みとこれまでこのお茶碗が利休をはじめ数々の人々の手に渡った歴史などを振り返ると、はたしてこの茶碗での一服はどんなお抹茶の味がするのだろうか。なんて想像するのですが、いろいろな緊張感の中での一服でもはや味がわからなくなってる気もして、想像ばかりがどんどん膨らむ茶碗でありました。

それではごきげんよう(スタッフY)

The other day, I heard that a black tea bowl by the first-generation Rakuchō Jirō was sold at auction for a staggering 800 million yen.

800 million yen… Its signature reads “Kankyo,” and faintly within the foot rim is the Rikyū seal. The characters on the lid cover are inscribed as “Sen no Rikyū, with utmost respect from Itō.” It is a masterpiece among masterpieces. Though I only saw it in pictures, faced with such an extraordinary masterpiece, I found myself drawn in, gazing at it for a while, hoping to gain some inspiration. But my lack of knowledge and refinement made it hard to express anything meaningful. All I could manage was a gasp of awe, “800 million yen…?”

From the image, it appears to be an extremely simple black Raku tea bowl. Yet, layers of color subtly overlap, their gradations sparking endless imagination. Traces of long-used tea stains remain, along with Rikyu’s fading seal. If I could hold it, I imagine I’d tremble—it’s that kind of masterpiece. Even so, I can’t express it well, and frankly, I feel intimidated just trying lol.

Incidentally, for some reason, no documents seem to exist describing the life of the first Chōjirō during his own era, so we don’t know what kind of person he was. His birth year is unknown, and he is said to have died in Tenshō 17 (1589). He was likely a member of a potter’s family.

How this first Chōjirō met Sen no Rikyū is also a mystery, of course. But records like the Tenshō 14th year tea gathering notes mention Chōjirō’s bowls. Perhaps Sen no Rikyū became increasingly captivated by these bowls, different from previous masterpieces, bowls that embodied his values and ideals. Oh dear, the weight of 800 million yen is even stimulating my poor imagination.

The exact number of works by the first Chōjirō remains unconfirmed, but it is estimated that only a few dozen tea bowls survive today. Raku Chōjirō’s tea bowls were the first specifically crafted for the tea ceremony based on Sen no Rikyū’s creative vision. They come in two types: black Raku and red Raku, with their most defining characteristic being their hand-formed construction without the use of a potter’s wheel.

Among these bowls crafted according to Rikyū’s philosophy, the representative pieces believed to have been owned and inscribed by Rikyū himself are called the “Seven Types of Chōjirō” or the “Seven Types of Rikyū,” and they have been particularly treasured. Within these “Seven Types of Chōjirō,” there seem to be an Inner Seven Types and an Outer Seven Types. The “Kankyū” that was recently auctioned off appears to be one piece from the Outer Seven Types. It is also counted among the “Newly Selected Seven Types of Chōjirō” chosen by the tea master Kanamori Tokusui. This “Kankyū” bowl had been missing until its appearance in this auction, and that very background somehow piques one’s curiosity.

While I can only speculate, reflecting on the weight of 800 million yen and the history of this bowl passing through the hands of Rikyu and many others, I wonder what kind of matcha flavor one would experience from a bowl like this. Yet, amidst all the tension, I suspect the taste might become indistinguishable, making this a bowl that only fuels ever-expanding imagination.

Well then, take care (Staff Y)

**********************

ご実家の整理やお片付けなどをされている方のご相談などが多くございます。

お片付けなどくれぐれもご無理のないようになさってくださいませ。

風光舎では古美術品や骨董品の他にも絵画や宝石、趣味のお品など様々なジャンルのものを買受しております。

お片付けをされていて、こういうものでもいいのかしらと迷われているものでも、どうぞお気軽にご相談下さいませ。

また風光舎は、出張買取も強化しております。ご近所はもちろん、愛知県内、岐阜県、三重県その他の県へも出張いたします。

まずは、お電話お待ちしております。

愛知県名古屋市千種区姫池通

骨董 買取【古美術 風光舎 名古屋店】

TEL052(734)8444

10:00-18:00 OPEN

土塁も残っています

土塁も残っています